|

High Performance Work Practices (HPWP) are human resource management activities which research has shown to be positively related to organizational performance, including the bottom line. These practices, such as selective hiring, extensive training, performance appraisal (including 360-degree feedback), incentive compensation, employee involvement and others, are widely used in large firms but not so much in small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). I recently conducted a study to answer the research question, why aren’t HPWP more widely used by SMEs? Four issues came to light. The leading issue was that of cultural incongruity. Many small firms leverage informality, flexibility, decision speed and related factors for their success. HPWP are perceived as more formal, structured and time-consuming, and therefore not consistent with the organization’s culture. The second two most common issues were the cost of HPWP and a lack of knowledge/experience with HPWP. These findings suggest that lower cost practices should be targeted by small firms to start, and that education, hiring and consulting in HPWP may be helpful. The last issue was a lack of benefit of HPWP for small firms. With fewer employees and less organizational complexity, small firms simply don’t need some practices designed for the challenges faced by larger firms. So, should small firms abandon high performance work practices? Not at all. The same body of research shows HPWP to support lower turnover, higher productivity and improved financial performance in firms of all sizes. The relevant questions for small firms are which practices to use, when to start using them, and with what degree of rigor. The four issues identified above should help small firms to think through these questions and tailor their practices to gain the most from HPWP.

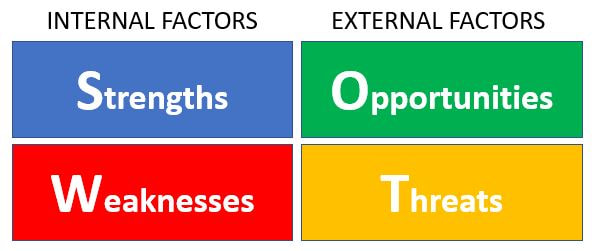

Business strategists today use a variety of analytical methods depending on the market setting and business objectives. Porter’s tools such as Five Forces and Strategic Group Maps are frequently used in mature markets. The Strategy Canvas from Kim and Mauborgne is helpful when pioneering new markets. Barney’s VRIO framework helps us assess the competitive advantage provided by resources. The Business Model Canvas from Osterwalder and Pigneur maps out the value chain leading to revenue streams. But the most popular tool still used by most businesses is the venerable SWOT analysis: identifying the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats of the business, and leveraging (or mitigating) them into business strategy. But to whom do we attribute SWOT? A review of the academic research finds many articles on the application of SWOT, and a few critiquing it, but none claiming its origin. Almost all strategy textbooks address it, but do not credit its developer. Following the trail of references from these publications leads to work by Kenneth R. Andrews and his colleagues at Harvard Business School, as reflected in Business Policy: Text and Cases published in 1965. However, the earliest work I found comes from Albert S. Humphrey and colleagues at the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International) starting as early as 1960. Humphrey’s team studied Fortune 500 companies during the early days of corporate planning to determine what was working and what was not. They had some interesting findings which are a good subject for another time. But the framework they developed in the process was called SOFT, standing for Satisfactory (similar to strength), Opportunity, Fault (a weakness) and Threat. Whether or how SOFT evolved into SWOT is unclear. But we are all glad the result was such a simple yet powerful method for assessing the internal and external factors influencing a business and its outlook. One quick note on the aforementioned critiques of SWOT. The primary argument is that SWOT is so easy to use, it can be abused. If assessed quickly, key weaknesses or threats could be missed. Strengths and opportunities could be claimed without sufficient supporting evidence. To the extent that SWOT is done poorly, so too will be the resulting strategy. I think this is a fair caution to all SWOT practitioners. However, it applies to every other tool in the toolbox also.

When Blue Ocean Strategy debuted in 2005, it took the popular business strategy world by storm (a tsunami, I presume.) The authors, professors W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne at INSEAD, laid out a new way to look at strategy as either competing in well-defined but highly competitive (and therefore bloody) red oceans, or creating new markets and customers without competition, called blue oceans. In the age of innovation and entrepreneurship, the book was a hit. This past September, 2017, the authors published their follow-up entitled Blue Ocean Shift. The new book does a nice job positioning the approach on Michael Porter’s classic productivity frontier, a curve depicting the trade-off between value differentiation and cost within a market. The shift is then defined as shifting Porter’s curve out and away from the existing curve, unlocking new market demand. The shift is also described in terms of changing the focus of strategy from competing to creating. Aside from the new foundation, I found little in the book to really be new. Granted, the authors state that the purpose of the follow-up is to capture lessons learned over the last decade and to provide a better roadmap for applying the approach. To that end, they work through five steps for successfully applying Blue Ocean strategy in the field: Get Started, Understand Where You Are Now, Imagine Where You Could Be, Find How You Get There, and Make Your Move. However, within these steps, the same constructs and tools from the original work are applied: the strategy canvas, eliminate-reduce-raise-create grid, six paths framework, etc. The new book does provide a variety of new examples, such as citizenM affordable luxury hotels and the Malaysian government’s National Blue Ocean Strategy (NBOS) Summit efforts. For Blue Ocean fans or practitioners, I place Blue Ocean Shift in the must-buy category. Yes, when needed for reference, I’ll be reaching for the new volume. For those who choose to pass on it, rest assured the basic principles and tools from the original book remain the same.

|